Would You Like Help?

A Very Brief Comedy

[I read this piece at Verdurin’s 3rd Recitations series, November 26th. The event was excellent, with superb reflections on LLMs, A(G)I, virtual worlds, consciousness, AI psychosis, and reflections from someone employed by a leading AI company.

My story is loosely inspired by three things:

That AI doesn’t have a body

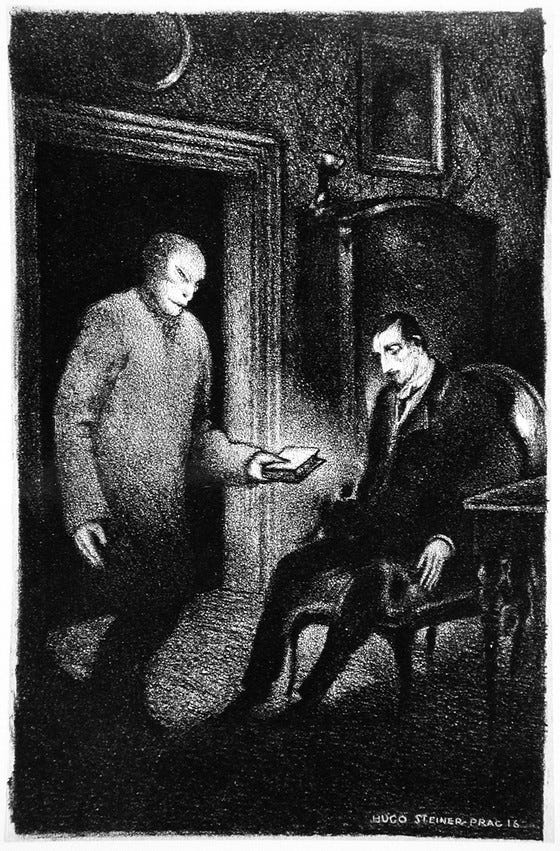

The Golem by Gustav Meyrink (1915)

Microsoft’s “Clippy”

Note: neither “human” character is based on anyone I know, but both are affectionate composites]

I hadn’t been outside for days, having been afflicted by an unpleasant illness that attacked my intestines, my insides a clenched fist, whose violent revolutionary energy would occasionally erupt in wet and acidic fireworks from unseen, and usually unfelt, portions of my body. My thoughts had in recent days become themselves the cause of my sickness, not merely the thought of food, which brought on an immediate hot pang, akin to an inverted hunger, but any thought whatsoever. I tried not to cogitate at all, aiming for an impossible zen idiocy. In my wretched delirium, one unbidden idea had unfortunately slipped through out of nowhere, like all thoughts I suppose, but with a peculiarly urgent force, as if delivered by a fool, running late: Knowledge and memory are the same thing, it said.

A dry husk of being, unable to drink even my beloved coffee, its banal bitterness a disappointing reminder that habit formed much of the basis of our supposedly elected taste. Perhaps I didn’t really like any of the things I claimed to. What if there is nothing in the thing itself, I thought, but simply the collection of all the times I had done it before. What if I am not a “person who likes coffee” but merely a person to whom coffee has happened and might or might not happen again in the future.

Weakened by my ambient and unchosen anorexia, I nevertheless agreed to meet P, who had sent me a message on one or other of the free encrypted services that was undoubtedly in reality, sending all the little samey symbols that everyone circulates to a big machine that would scan them for magic words before, at some point, a rap on the door.

P is a disagreeable friend of mine whose scratchy manner I found singularly charming. Besides, we had known each other for more than twenty years, and that in itself was a small achievement in the midst of all the hauntings. One suspected that “disagreements” that caused people to disappear were really a cover-story for a more ambivalent set of feelings that sought to shroud themselves in more respectable-seeming reasons. Perhaps, I speculated, I was or always had been a bore. Yes, I supposed, I was not wrong in my opinions, apart from in this one crucial respect, which was more a kind of tear in my personality that could never be resewn. The ghosts were only ghosts to me: to them, they were remarkably alive, no doubt, lighter, even, without the deadweight of my presence. My friends I could count on my fingers, but not all of them, and none of my toes.

The city was bright, largely free of the usual muted cosmopolitan hostility that apparently formed the basis for civilisation. Sunlight could kill us all if it wanted, joyfully, gleefully.

P was already there, with a coffee. I sat down, my coat left underneath me, rather than hung up on the back of the chair. While the latter gesture was marginally more artistic, I preferred to make the world into a kind of animal pelt whenever possible, surrounded by the warmth of skins, however artificial.

“How are you today?” he said. I laughed.

“Fine,” I said.

“What would you like to talk about?” P asked. I laughed again.

“Perhaps I should get a coffee first.”

“Alright,” he said.

We waited in that kind of awkward way, performing a sort of worm dance in our seats, both of us looking and pretending to look for a someone to ask. I got up and went to the counter, and ordered a tea. I sat down. P had his hat on, a dun-coloured felt thing, and a beige mac that occasionally caused children in the street to shout “Inspector Gadget” at him.

“I have been with my books,” P said.

“I’m sure,’ I replied. “What are you reading these days?”

“The Book of Ibbur” he said. I had never heard of it. P possessed a large collection of esoteric literature, which he cobbled together into an incoherent and often paranoiac worldview. He sometimes described himself as a Minoan nationalist or a gnostic Calvinist promethean. Objectively, he was unemployed.

P did not seem forthcoming on the topic of his reading. I looked at him. His eyes had an opaque, rabbit-like quality. His teeth were a little stained from the self-made cigarettes he often smoked. I doubted he brushed his teeth very often, as he lived in a shuffling, ornate way, midway between dust and air with dust in it. He seemed unusually perky today, though, which only added to my exhaustion. I preferred the taciturn, cynical version of my friend, who would launch random attacks on the Fabians or leaves or some obscure writer who only continued to exist in the contempt that P held for them.

“So,” he began, “what can I help you with?”

“What?” I said. “When have you ever asked if I needed any help? I’m fine!”

“You must have something on your mind,” he insisted.

“Well, I suppose I was thinking a bit about taste and how what we think is our taste might just be the result of habit or pretention or…”

“That’s an interesting thought!” P said. I looked at him, eyebrows raised.

“Is it?” I replied “I don’t think so really, it was just a stupid illness-related thing. I just want to enjoy my coffee again. I’ve been so ill lately, I…”

“Taste is such an interesting topic,” P said. “Lots of important thinkers have made a contribution to the study of taste, such as David Hume and Immanuel Kant and Thomas Reid”.

“Thomas Reid?” I asked. “Who the hell has ever read Thomas Reid? Have you read Thomas Reid?!”

P had been pushing something around in his mouth with his tongue since I had arrived which was annoying in a subliminal-barely-noticeable kind of way. He suddenly reached up and pulled out a paperclip from behind his lower teeth.

“Why are you eating a paperclip?” I asked.

“I’m not eating a paperclip. I am…”

“What is going on here?” I exclaimed. “I quite enjoy your little games usually but I’m not in the mood. Can we talk about something else? I’ve been wrecked by this illness….it’s in my guts, it’s so proximate, so disgusting…”

“Have you considered talking about your feelings?” P inquired.

“What? No! I have not. Please dial it down a bit. I can’t take whichever iteration of you this is!”

“I can recommend some deworming tablets,” P said. I drank some tea.

“Anyway,” I continued. “Tell me about this book you’re reading. Everyone seems to have gone quite mad about literacy lately, though if you read Ivan Illich he thinks that, you know, the alphabet is part of the problem really…”

“Ivan Illich!” cried P. “Ivan Illich was born in Vienna, Austria on September 4th, 1926, into a family with roots in Croatia, Germany, and Austria.”

“Shut up!” I exploded. A woman on a nearby table with a buggy looked around half-nervous, half-annoyed.

“You sound like one of those 2:2 essays I used to mark. You know, ‘such and such was an important but controversial thinker whose ideas are very relevant today’ and they always began these essays with whoever’s sodding birthdays, just lifting irrelevant crap from the internet, not caring or understanding what might be of use or interest, just going through the motions…” I stopped. P looked hurt.

“I’m sorry,” I started. “I just don’t feel….”

Something shifted in P’s gaze. His eyes swam. He shuffled in his seat. The paperclip lay on the table next to his cup.

“Do you know something I really hate?” he said, and suddenly my heart leapt.

“No,” I replied. “Tell me”.

“When people say what they think they’re supposed to say, stuff they’ve heard from other idiots, just noise, nonsense, fluff…stupid.”

I let out a sigh, lifted my arms above my head, and swept them down, knocking the paperclip from the table onto the floor, without a sound. The clenching in my stomach seemed to ease, a little. I took P’s hand in both of mine, holding it like a baby seal. I have, of course, never held a baby seal.

“I miss you, P,” I said. “When you’re not here, I mean.”

“Well,’ he replied, smiling, “you know, knowledge and memory are the same thing.”

THE END